TypeScript

1 Introduction

Web applications such as e-mail, maps, document editing, and collaboration tools are becoming an increasingly important part of the everyday computing. We designed TypeScript to meet the needs of the JavaScript programming teams that build and maintain large JavaScript programs such as web applications. TypeScript helps programming teams to define interfaces between software components and to gain insight into the behavior of existing JavaScript libraries. TypeScript also enables teams to reduce naming conflicts by organizing their code into dynamically-loadable modules. TypeScript’s optional type system enables JavaScript programmers to use highly-productive development tools and practices: static checking, symbol-based navigation, statement completion, and code re-factoring.

TypeScript is a syntactic sugar for JavaScript. TypeScript syntax is a superset of Ecmascript 5 (ES5) syntax. Every JavaScript program is also a TypeScript program. The TypeScript compiler performs only file-local transformations on TypeScript programs and does not re-order variables declared in TypeScript. This leads to JavaScript output that closely matches the TypeScript input. TypeScript does not transform variable names, making tractable the direct debugging of emitted JavaScript. TypeScript optionally provides source maps, enabling source-level debugging. TypeScript tools typically emit JavaScript upon file save, preserving the test, edit, refresh cycle commonly used in JavaScript development.

TypeScript syntax includes several proposed features of Ecmascript 6 (ES6), including classes and modules. Classes enable programmers to express common object-oriented patterns in a standard way, making features like inheritance more readable and interoperable. Modules enable programmers to organize their code into components while avoiding naming conflicts. The TypeScript compiler provides module code generation options that support either static or dynamic loading of module contents.

TypeScript also provides to JavaScript programmers a system of optional type annotations. These type annotations are like the JSDoc comments found in the Closure system, but in TypeScript they are integrated directly into the language syntax. This integration makes the code more readable and reduces the maintenance cost of synchronizing type annotations with their corresponding variables.

The TypeScript type system enables programmers to express limits on the capabilities of JavaScript objects, and to use tools that enforce these limits. To minimize the number of annotations needed for tools to become useful, the TypeScript type system makes extensive use of type inference. For example, from the following statement, TypeScript will infer that the variable ‘i’ has the type number.

var i = 0;

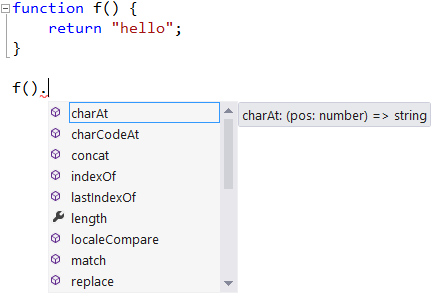

TypeScript will infer from the following function definition that the function f has return type string.

function f() {

return "hello";

}

To benefit from this inference, a programmer can use the TypeScript language service. For example, a code editor can incorporate the TypeScript language service and use the service to find the members of a string object as in the following screen shot.

In this example, the programmer benefits from type inference without providing type annotations. Some beneficial tools, however, do require the programmer to provide type annotations. In TypeScript, we can express a parameter requirement as in the following code fragment.

function f(s: string) {

return s;

}

f({}); // Error

f("hello"); // Ok

This optional type annotation on the parameter ‘s’ lets the TypeScript type checker know that the programmer expects parameter ‘s’ to be of type ‘string’. Within the body of function ‘f’, tools can assume ‘s’ is of type ‘string’ and provide operator type checking and member completion consistent with this assumption. Tools can also signal an error on the first call to ‘f’, because ‘f’ expects a string, not an object, as its parameter. For the function ‘f’, the TypeScript compiler will emit the following JavaScript code:

function f(s) {

return s;

}

In the JavaScript output, all type annotations have been erased. In general, TypeScript erases all type information before emiting JavaScript.

1.1 Ambient Declarations

An ambient declaration introduces a variable into a TypeScript scope, but has zero impact on the emitted JavaScript program. Programmers can use ambient declarations to tell the TypeScript compiler that some other component will supply a variable. For example, by default the TypeScript compiler will print an error for uses of undefined variables. To add some of the common variables defined by browsers, a TypeScript programmer can use ambient declarations. The following example declares the ‘document’ object supplied by browsers. Because the declaration does not specify a type, the type ‘any’ is inferred. The type ‘any’ means that a tool can assume nothing about the shape or behavior of the document object. Some of the examples below will illustrate how programmers can use types to further characterize the expected behavior of an object.

declare var document;

document.title = "Hello";

// Ok

because document has been declared

In the case of ‘document’, the TypeScript compiler automatically supplies a declaration, because TypeScript by default includes a file ‘lib.d.ts’ that provides interface declarations for the built-in JavaScript library as well as the Document Object Model.

The TypeScript compiler does not include by default an interface for jQuery, so to use jQuery, a programmer could supply a declaration such as:

declare var $;

Section 1.3 provides a more extensive example of how a programmer can add type information for jQuery and other libraries.

1.2 Function Types

Function expressions are a powerful feature of JavaScript. They enable function definitions to create closures: functions that capture information from the lexical scope surrounding the function’s definition. Closures are currently JavaScript’s only way of enforcing data encapsulation. By capturing and using environment variables, a closure can retain information that cannot be accessed from outside the closure. JavaScript programmers often use closures to express event handlers and other asynchronous callbacks, in which another software component, such as the DOM, will call back into JavaScript through a handler function.

TypeScript function types make it possible for programmers to express the expected signature of a function. A function signature is a sequence of parameter types plus a return type. The following example uses function types to express the callback signature requirements of an asynchronous voting mechanism.

function vote(candidate: string,

callback: (result: string)

=> any) {

// ...

}

vote("BigPig",

function(result: string) {

if (result === "BigPig") {

// ...

}

}

);

In this example, the second parameter to ‘vote’ has the function type

(result: string) => any

which means the second parameter is a function returning type ‘any’ that has a single parameter of type ‘string’ named ‘result’.

Section 3.7.2 provides additional information about function types.

1.3 Object Types

TypeScript programmers use object types to declare their expectations of object behavior. The following code uses an object type literal to specify the return type of the ‘MakePoint’ function.

var MakePoint: () => {

x: number; y: number;

};

Programmers can give names to object types; we call named object types interfaces. For example, in the following code, an interface declares one required field (name) and one optional field (favoriteColor).

interface Friend {

name: string;

favoriteColor?: string;

}

function add(friend: Friend) {

var name = friend.name;

}

add({ name: "Fred" }); // Ok

add({ favoriteColor: "blue"

}); // Error, name required

add({ name: "Jill",

favoriteColor: "green"

}); // Ok

TypeScript object types model the diversity of behaviors that a JavaScript object can exhibit. For example, the jQuery library defines an object, ‘$’, that has methods, such as ‘get’ (which sends an Ajax message), and fields, such as ‘browser’ (which gives browser vendor information). However, jQuery clients can also call ‘$’ as a function. The behavior of this function depends on the type of parameters passed to the function.

The following code fragment captures a small subset of jQuery behavior, just enough to use jQuery in a simple way.

interface JQuery {

text(content: string);

}

interface JQueryStatic {

get(url: string, callback:

(data: string) => any);

(query: string): JQuery;

}

declare var $: JQueryStatic;

$.get("http://mysite.org/divContent",

function (data: string) {

$("div").text(data);

}

);

The ‘JQueryStatic’ interface references another interface: ‘JQuery’. This interface represents a collection of one or more DOM elements. The jQuery library can perform many operations on such a collection, but in this example the jQuery client only needs to know that it can set the text content of each jQuery element in a collection by passing a string to the ‘text’ method. The ‘JQueryStatic’ interface also contains a method, ‘get’, that performs an Ajax get operation on the provided URL and arranges to invoke the provided callback upon receipt of a response.

Finally, the ‘JQueryStatic’ interface contains a bare function signature

(query: string): JQuery;

The bare signature indicates that instances of the interface are callable. This example illustrates that TypeScript function types are just special cases of TypeScript object types. Specifically, function types are object types that contain only a call signature, but no properties. For this reason we can write any function type as an object type literal. The following example uses both forms to describe the same type.

var f: { (): string; };

var sameType: () => string = f; //

Ok

var nope: () => number = sameType; // Error: type mismatch

We mentioned above that the ‘$’ function behaves differently depending on the type of its parameter. So far, our jQuery typing only captures one of these behaviors: return an object of type ‘JQuery’ when passed a string. To specify multiple behaviors, TypeScript supports overloading of function signatures in object types. For example, we can add an additional call signature to the ‘JQueryStatic’ interface.

(ready: () => any): any;

This signature denotes that a function may be passed as the parameter of the ‘$’ function. When a function is passed to ‘$’, the jQuery library will invoke that function when a DOM document is ready. Because TypeScript supports overloading, tools can use TypeScript to show all available function signatures with their documentation tips and to give the correct documentation once a function has been called with a particular signature.

A typical client would not need to add any additional typing but could just use a community-supplied typing to discover (through statement completion with documentation tips) and verify (through static checking) correct use of the library, as in the following screen shot.

Section 3.3 provides additional information about object types.

1.4 Structural Subtyping

Object types are compared structurally. For example, in the code fragment below, class ‘CPoint’ matches interface ‘Point’ because ‘CPoint’ has all of the required members of ‘Point’. A class may optionally declare that it implements an interface, so that the compiler will check the declaration for structural compatibility. The example also illustrates that an object type can match the type inferred from an object literal, as long as the object literal supplies all of the required members.

interface Point {

x: number;

y: number;

}

function getX(p: Point) {

return p.x;

}

class CPoint {

x: number;

y: number;

constructor(x: number,

y: number) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

}

getX(new CPoint(0, 0)); // Ok, fields match

getX({ x: 0, y: 0, color: "red" }); // Extra fields Ok

getX({ x: 0 }); // Error: supplied parameter does not match

See Section 3.8 for more information about type comparisons.

1.5 Contextual Typing

Ordinarily, TypeScript type inference proceeds “bottom-up”: from the leaves of an expression tree to its root. In the following example, TypeScript infers ‘number’ as the return type of the function ‘mul’ by flowing type information bottom up in the return expression.

function mul(a: number, b: number) {

return a * b;

}

For variables and parameters without a type annotation or a default value, TypeScript infers type ‘any’, ensuring that compilers do not need non-local information about a function’s call sites to infer the function’s return type. Generally, this bottom-up approach provides programmers with a clear intuition about the flow of type information.

However, in some limited contexts, inference proceeds “top-down” from the context of an expression. Where this happens, it is called contextual typing. Contextual typing helps tools provide excellent information when a programmer is using a type but may not know all of the details of the type. For example, in the jQuery example, above, the programmer supplies a function expression as the second parameter to the ‘get’ method. During typing of that expression, tools can assume that the type of the function expression is as given in the ‘get’ signature and can provide a template that includes parameter names and types.

$.get("http://mysite.org/divContent",

function (data) {

$("div").text(data);

// TypeScript infers data is a string

}

);

Contextual typing is also useful for writing out object literals. As the programmer types the object literal, the contextual type provides information that enables tools to provide completion for object member names.

Section 4.18 provides additional information about contextually typed expressions.

1.6 Classes

JavaScript practice has at least two common design patterns: the module pattern and the class pattern. Roughly speaking, the module pattern uses closures to hide names and to encapsulate private data, while the class pattern uses prototype chains to implement many variations on object-oriented inheritance mechanisms. Libraries such as ‘prototype.js’ are typical of this practice.

This section and the module section below will show how TypeScript emits consistent, idiomatic JavaScript code to implement classes and modules that are closely aligned with the current ES6 proposal. The goal of TypeScript’s translation is to emit exactly what a programmer would type when implementing a class or module unaided by a tool. This section will also describe how TypeScript infers a type for each class declaration. We’ll start with a simple BankAccount class.

class BankAccount {

balance = 0;

deposit(credit: number) {

this.balance +=

credit;

return this.balance;

}

}

This class generates the following JavaScript code.

var BankAccount = (function

() {

function BankAccount() {

this.balance = 0;

}

BankAccount.prototype.deposit = function(credit)

{

this.balance +=

credit;

return this.balance;

};

return BankAccount;

})();

This TypeScript class declaration creates a variable named ‘BankAccount’ whose value is the constructor function for ‘BankAccount’ instances. This declaration also creates an instance type of the same name. If we were to write this type as an interface it would look like the following.

interface BankAccount {

balance: number;

deposit(credit: number): number;

}

If we were to write out the function type declaration for the ‘BankAccount’ constructor variable, it would have the following form.

var BankAccount: new() => BankAccount;

The function signature is prefixed with the keyword ‘new’ indicating that the ‘BankAccount’ function must be called as a constructor. It is possible for a function’s type to have both call and constructor signatures. For example, the type of the built-in JavaScript Date object includes both kinds of signatures.

If we want to start our bank account with an initial balance, we can add to the ‘BankAccount’ class a constructor declaration.

class BankAccount {

balance: number;

constructor(initially: number) {

this.balance =

initially;

}

deposit(credit: number) {

this.balance +=

credit;

return this.balance;

}

}

This version of the ‘BankAccount’ class requires us to introduce a constructor parameter and then assign it to the ‘balance’ field. To simplify this common case, TypeScript accepts the following shorthand syntax.

class BankAccount {

constructor(public balance: number) {

}

deposit(credit: number) {

this.balance +=

credit;

return this.balance;

}

}

The ‘public’ keyword denotes that the constructor parameter is to be retained as a field. Public is the default visibility for class members, but a programmer can also specify private visibility for a class member. Private visibility is a design-time construct; it is enforced during static type checking but does not imply any runtime enforcement.

TypeScript classes also support inheritance, as in the following example.

class CheckingAccount extends BankAccount {

constructor(balance: number) {

super(balance);

}

writeCheck(debit: number) {

this.balance -= debit;

}

}

In this example, the class ‘CheckingAccount’ derives from class ‘BankAccount’. The constructor for ‘CheckingAccount’ calls the constructor for class ‘BankAccount’ using the ‘super’ keyword. In the emitted JavaScript code, the prototype of ‘CheckingAccount’ will chain to the prototype of ‘BankingAccount’.

TypeScript classes may also specify static members. Static class members become properties of the class constructor.

Section 8 provides additional information about classes.

1.7 Modules

Classes and interfaces support large-scale JavaScript development by providing a mechanism for describing how to use a software component that can be separated from that component’s implementation. TypeScript enforces encapsulation of implementation in classes at design time (by restricting use of private members), but cannot enforce encapsulation at runtime because all object properties are accessible at runtime. Future versions of JavaScript may provide private names which would enable runtime enforcement of private members.

In the current version of JavaScript, the only way to enforce encapsulation at runtime is to use the module pattern: encapsulate private fields and methods using closure variables. The module pattern is a natural way to provide organizational structure and dynamic loading options by drawing a boundary around a software component. A module can also provide the ability to introduce namespaces, avoiding use of the global namespace for most software components.

The following example illustrates the JavaScript module pattern.

(function(exports) {

var key = generateSecretKey();

function sendMessage(message) {

sendSecureMessage(message, key);

}

exports.sendMessage = sendMessage;

})(MessageModule);

This example illustrates the two essential elements of the module pattern: a module closure and a module object. The module closure is a function that encapsulates the module’s implementation, in this case the variable ‘key’ and the function ‘sendMessage’. The module object contains the exported variables and functions of the module. Simple modules may create and return the module object. The module above takes the module object as a parameter, ‘exports’, and adds the ‘sendMessage’ property to the module object. This augmentation approach simplifies dynamic loading of modules and also supports separation of module code into multiple files.

The example assumes that an outer lexical scope defines the functions ‘generateSecretKey’ and ‘sendSecureMessage’; it also assumes that the outer scope has assigned the module object to the variable ‘MessageModule’.

TypeScript modules provide a mechanism for succinctly expressing the module pattern. In TypeScript, programmers can combine the module pattern with the class pattern by nesting modules and classes within an outer module.

The following example shows the definition and use of a simple module.

module M {

var s = "hello";

export function f() {

return s;

}

}

M.f();

M.s; // Error, s is not exported

In this example, variable ‘s’ is a private feature of the module, but function ‘f’ is exported from the module and accessible to code outside of the module. If we were to describe the effect of module ‘M’ in terms of interfaces and variables, we would write

interface M {

f(): string;

}

var M: M;

The interface ‘M’ summarizes the externally visible behavior of module ‘M’. In this example, we can use the same name for the interface as for the initialized variable because in TypeScript type names and variable names do not conflict: each lexical scope contains a variable declaration space and type declaration space (see Section 2.3 for more details).

Module ‘M’ is an example of an internal module, because it is nested within the global module (see Section 9 for more details). The TypeScript compiler emits the following JavaScript code for this module.

var M;

(function(M) {

var s = "hello";

function f() {

return s;

}

M.f = f;

})(M||(M={}));

In this case, the compiler assumes that the module object resides in global variable ‘M’, which may or may not have been initialized to the desired module object.

TypeScript also supports external modules, which are files that contain top-level export and import directives. For this type of module the TypeScript compiler will emit code whose module closure and module object implementation vary according to the specified dynamic loading system, for example, the Asynchronous Module Definition system.

TypeScript Language Specification (converted to HTML pages by @Bartvds)

Version 0.9.1

August 2013

Microsoft is making this Specification available under the Open Web Foundation Final Specification Agreement Version 1.0 ('OWF 1.0') as of October 1, 2012. The OWF 1.0 is available at http://www.openwebfoundation.org/legal/the-owf-1-0-agreements/owfa-1-0.

TypeScript is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation.